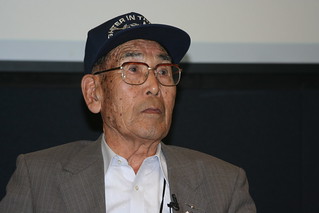

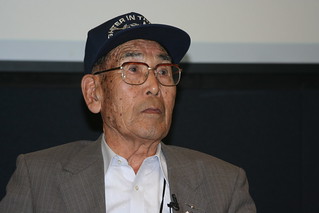

Kaname Harada

|

FORD ISLAND — On Friday afternoon 23 members of the Unabarakai, an organization of World War II Navy pilots who fought for Japan, attended a Battle of Midway symposium at the Pacific Aviation Museum on Ford Island. The Battle of Midway is considered the turning point in the War of the Pacific. Up until then the United States had been losing, often badly, and Japan had been consistently winning. Japan, with its string of victories, was suffering from overconfidence and belief in its own propaganda.

All four of the participating Japanese aircraft carriers were destroyed on the first day of the battle, June 4, 1942. The four were among the six that had taken part in the Pearl Harbor attack. Carriers were very important in the fighting prowess of the two sides.

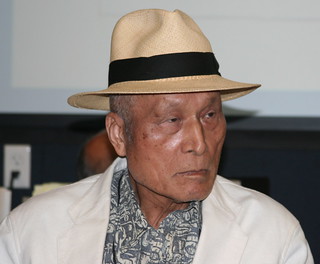

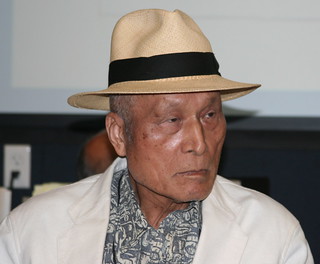

Two of Unabarakai’s members, Kaname Harada, 93, and Jiro Yoshida, 85, were featured in Friday’s symposium at the Museum. Both were WWII Zero pilots. Jiro joined the Imperial Navy in 1943, after the Battle of Midway.

Jiro Yoshida

|

Kaname, a future ace, graduated from naval flight school in 1937, first in his class. To honor the occasion, Emperor Hirohito gave him a large silver pocket watch, which he still has.

Kaname was Shigenori Nishikaichi’s flight instructor. Nishikaichi was the pilot who crash-landed on Niihau right after the Pearl Harbor attack in what became known as the Niihau Incident. That event is suspected of playing a precipitating part in the decision to move ethnic Japanese out of the west coast of the United States through an executive order signed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Kaname told his story of the Battle of Midway in a question and answer impromptu session after the symposium ended.

On June 4, 1942, he recounted, the first day of the battle, he lifted off at the crack of dawn in his Zero from the aircraft carrier Soryu. His assignment was not to attack, but to defend the carrier. In the process of doing so, he shot down five torpedo bombers. While he was in the air the Soryu was sunk by the Americans, so he landed his bullet-riddled and badly damaged plane on the Hiryu, the sole remaining carrier of the four taking part in the battle. The other three had been hit and were unusable for a landing. Harada's plane was dumped over the side as useless while he quickly began a meal to replenish his energy as another plane was readied for him. While still wolfing down his food, a crew member yelled to him that his new plane was ready. He rushed off to rejoin the battle. As he took off in his replacement plane and reached a point about 800 yards from the carrier, the ship was hit and, with further hits, mortally damaged with flames reaching high, making it impossible to return with his plane. Now all four carriers had been crippled by explosions and were either sinking or already sunk. The sight of the four mortally damaged carriers, the pride of the Imperial Navy, in their death throes was a deeply discouraging sight.

With no carriers left to land on, Harada flew around in circles, expecting certain death. He thought back regretfully to the pistol that he had placed on the table while he ate in haste on the Hiryu. When he had rushed off to climb into his replacement plane, the urgency of the moment had caused him to forget the pistol that he had placed to the side. Now, facing what he thought would be a short and unpleasant prelude to certain death, he wished he had the pistol so that he could put a bullet through his brain. Other pilots were in the same position as he, but they had their pistols. Harada thinks that’s the way some of them ended their lives.

When Harada’s fuel was about to run out, he spotted a destroyer that was leaving a wide wake. He made a water landing in that wake. His watch stopped as he hit the water at 3:35 p.m. Japan time, which would be 7:35 p.m. Midway time. (Military men on battle assignments kept their time pieces set to Japan time no matter where they were.) His heart lifted as he looked forward to a quick pickup. Instead, the destroyer was suddenly swarmed by American B-17s and it took off like a bat out of Hell. He was left in the water by himself with his best hope for life, the destroyer, gone. Three and a half hours passed. Suddenly in the darkness he spotted a ship that was flashing a dim recognition light in code. He recognized by the code that it was a Japanese ship and he splashed furiously to create the white water and bioluminescence that would attract the attention of those on the ship. He was successful, and the Makigumo, a destroyer, picked him up, saving his life. Having faced what he thought was certain death, he was a happy man.

But that quickly turned to horror as he came on deck. It was filled with men with missing hands and legs, men who were naked, whose faces were damaged beyond recognition. All of them appeared to have been burned. There was no place for Harada to place his feet without stepping on them. They were crying out, “Kurushii, kurushii!”, a word that doesn’t have a good English equivalent. An approximation would be, “I'm barely hanging in there. This is more than I can take.” The horribly mangled victims were begging for water. Some were calling out for their mothers. The voices of extreme suffering from the mass of war victims filled the air.

A doctor soon came to tend to Harada. Harada rejected his attention, saying, “I’m fine. Look after the people who really need it.”

The doctor replied that Harada was the appropriate patient, that he could be treated and soon returned to battle. The others were useless for the purpose of fighting.

In battle situations, Harada says, combatants were stripped of their humanity. Rather than being viewed as the human beings they were, they were instead looked upon as commodities, utilitarian war weapons. Men who were not severely injured were to be patched up a little to a serviceable condition and then quickly put back into action. The men who couldn’t be patched up were left to themselves, weapons that were no longer functional.

Harada's war experience turned him into someone who thoroughly detests war. He is completely against it.

After losing the Battle of Midway, its participants were sent back to Japan, where they were confined to a base for a month. They were not allowed to write or receive letters. The government didn’t want news of the defeat to get out and demoralize the troops and the people.

After the war was over, people like Harada, formerly part of the Japanese war machine, with a reputation, had great difficulty finding a job. He tried very hard, but in addition to the obstacle of his military past, times were extremely tough all over. He decided to establish a kindergarten. Today, at age 93, he is the principal of a kindergarten in Nagano prefecture. Although younger people tend to think of people of Harada's age as in their dotage, he is still sharp as a tack.

Looking back on his war experiences, Harada says he doesn’t regret his time in the military, but neither does he think of it as a good thing. It was a time of war for his country, he says, and it was his fate at that particular point in the flow of time to serve in the Japanese military, doing his best for his country.

In wartime Japan, he continues, when a man turned 20, he had a duty and legal obligation to be in the military. He could either join or be drafted. Harada joined. “From the time we were children,” he said, “we were brainwashed to believe that war was good and that whatever Japan did was right.”

He attended a get-together last year with American pilots at Iwakuni, an American Marine Corps Air Station in Yamaguchi prefecture, Japan. The pilots told him that they, too, didn’t like war.

The solution? Harada says, “Teach true, correct history, including the progression of events. It’s essential that children be taught this. That’s why I participate in symposiums like this [at the Pacific Air Museum]: to relate the reality of war. I tell my children, my grandchildren, the children in my school, what war is really like. Children are taught sugar-coated history: that’s the problem. They should be told the true state of affairs. If they understand that reality, I believe they won’t start wars. I do my part by teaching my kindergarteners. I tell them, 'treasure peace.'”

Links:

Japanese WWII pilots in Hawaii to commemorate Midway battle [The Honolulu Advertiser]

Zero ace recalls missions over Midway, Pearl Harbor [Honolulu Star-Bulletin]